Biographical Overview

"Because the field of medicine has been generally recognized and accepted as an ennobling and genuinely humanitarian field of endeavor, it constitutes one of the strongest bridges across international borders."

American surgeon Michael Ellis DeBakey was a legendary physician, educator, and medical statesman. During a career spanning 75 years, his work transformed cardiovascular surgery, raised medical education standards, and influenced national health care policy. He pioneered dozens of operative procedures such as aneurysm repair, coronary bypass, and endarterectomy, which routinely save thousands of lives each year, and performed some of the first heart transplants. His inventions included the roller pump (a key component of heart-lung machines) as well as artificial hearts and ventricular assist pumps. From the small Baylor University School of Medicine in Houston, he built a premier medical center, and there trained several generations of top surgeons from all over the world. For decades, his professional expertise and wisdom informed health care policy in the U.S. and abroad.

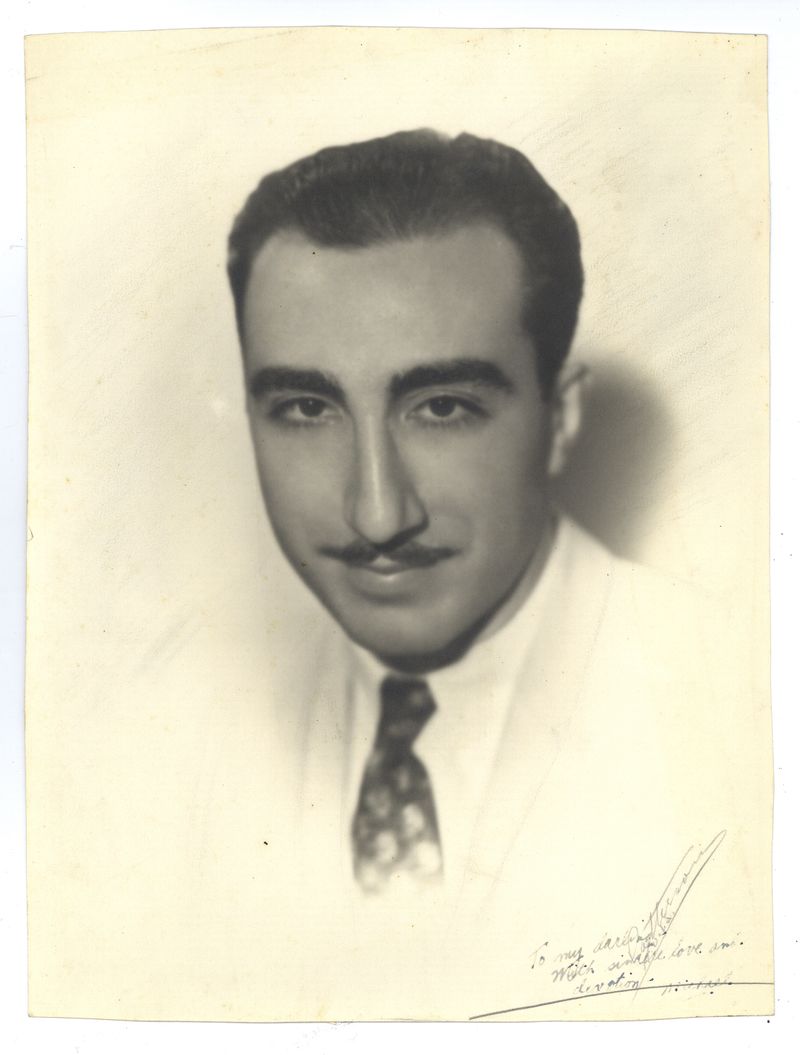

DeBakey was born on September 7, 1908, in Lake Charles, Louisiana, the oldest child of Lebanese immigrants Shaker Morris and Raheeja Debaghi (the name was later Anglicized.) His father was a businessman whose enterprises included several drugstores, and his mother was an accomplished seamstress who also taught sewing classes. Besides Michael, their family included his brother Ernest and sisters Lois, Selma, and Selena. DeBakey often recalled his childhood with affection. Both parents fostered a love of learning and discovery in their children, and instilled enormous self-discipline as well as compassion. The DeBakey children all excelled in school; Ernest, like his older brother, went on to become a surgeon, and Lois and Selma pioneered the field of scientific communication studies. Michael's boyhood interests were diverse: he studied biology, literature, French, and German; he played the saxophone, enjoyed activities with his Boy Scout troop, and raised prize-winning vegetables in his father's large garden. He also liked working with his hands; he and his brother took apart car engines and reassembled them, and his mother taught him to knit and sew. (By the age of ten he could cut his own shirts from patterns and assemble them.) He became interested in medicine through his acquaintance with the physicians who visited his father's drugstore, where he often worked after school.

At Tulane University, DeBakey finished his premedical courses in two years, entering the Tulane School of Medicine in 1928. There his experience working part-time in surgical research labs led him to choose an academic medical career. He was mentored by Rudolph Matas and Alton Ochsner, both of whom encouraged him to specialize in surgery. While still in medical school, DeBakey devised a roller pump that he used initially for blood transfusions; the pump later became an essential component of heart-lung machines. He earned his MD in 1932, and did an internship at Charity Hospital in New Orleans from 1933 to 1935. He also carried out research on stomach ulcers for which he received a MS in 1935. Encouraged by his mentors to get further surgical training in Europe, he studied for a year with René Leriche at the University of Strasbourg and then spent a year working with Martin Kirschner at Heidelberg University. Returning in 1937, he joined the Tulane faculty and married Diana Cooper, a nursing supervisor at Charity Hospital. They had four sons: Michael, Ernest, Barry, and Denis.

From 1942 to 1946, DeBakey served in the Surgical Consultants Division of the Army Surgeon General's Office, where he and his colleagues assessed the Army's European medical operations and formulated plans to improve surgical services. They developed the Auxiliary Surgical Groups to provide surgical care to wounded troops near the front lines. First deployed in 1943, these groups evolved into the Mobile Auxiliary Surgical Hospital (MASH) units that provided crucial care during the Korean and Vietnam conflicts. After the war ended, DeBakey stayed in service and helped to coordinate medical units to receive vast numbers of returning soldiers, until the Veterans Administration hospital system could be brought up to speed. He returned to Tulane in 1946, but spent several years shuttling to Washington to serve on the Medical Task Force of the first Hoover Commission, which was appointed to improve efficiency and effectiveness of government programs. DeBakey was also one of the primary architects of the National Research Council's Medical Follow-Up Agency, established in 1946 to enable follow-up studies on the health of veterans, using the vast medical records resources generated during the war.

In 1948, Baylor University College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, asked DeBakey to head its department of surgery. It was a small school, with no teaching hospital and no clinical faculty, and though it was the designated hub of a planned Texas Medical Center, that center hadn't yet materialized. Happy at Tulane, DeBakey was skeptical about taking the Baylor job, but finally took the chance. During his first years there, he set up a surgical residency program based in the newly opened VA hospital and the local charity hospital, upgraded the medical curriculum, established surgical research labs, raised funds for the medical school, and recruited qualified staff and faculty. In 1968 Baylor College of Medicine separated from Baylor University. DeBakey served as CEO, then as President from 1969 to 1979, then as Chancellor (1979-1986) and Chancellor Emeritus (1986-2008) while continuing as Chair of the Department of Surgery until 1993.

DeBakey's trailblazing surgical treatments for cardiovascular disease made him the world's best known surgeon and brought prestige to Baylor and its affiliated institutions. In 1952, he and Denton Cooley were the first Americans to successfully repair an abdominal aortic aneurysm, removing the weakened and distended section of the vessel and replacing it with a section of preserved cadaver aorta. (French surgeon Charles Dubost had done a similar operation the previous year.) They quickly applied the technique to progressively more difficult aneurysm repairs in the upper sections of the aorta. Within several years, they were fabricating the grafts from DuPont's new Dacron material, and DeBakey then helped design a special knitting machine to manufacture them. As the first heart-lung bypass machines were developed in the 1950s, DeBakey and his colleagues were among the first to use them to do open-heart operations. DeBakey also devised techniques to repair dissecting aneurysms, and was the first to successfully perform procedures such as carotid endarterectomy and patch-graft angioplasty. In 1964 he did the first successful coronary bypass operation, and in 1968, the first multiple-organ transplant. A notoriously demanding perfectionist in the operating room, DeBakey was calm and attentive with patients and their families, and routinely did post-operative rounds late into the evenings.

Despite the demands of surgery, teaching, and administrative duties, DeBakey (who rarely slept more than 5 hours per night) also devoted substantial time to surgical research and the development of total and partial mechanical hearts and cardiac assist devices. In 1966 he was the first to successfully implant a left ventricular bypass pump. DeBakey's prototypes for permanent mechanical total heart replacements did not advance beyond animal experimentation, however. During the 1980s and 1990s, he collaborated with NASA engineers to develop a miniaturized axial-flow ventricular assist device, the DeBakey VAD, now manufactured by MicroMed Technology, Inc.

DeBakey was also able to apply his considerable medical expertise and administrative skills to public policy, beginning just after World War II, when he served on the Medical Task Force of the first and second Hoover Commissions (1946-49 and 1953-55). He subsequently played a key role in initiating legislation to establish the National Library of Medicine (NLM) in 1956, and served for many years on the NLM Board of Regents. He advised many U.S. presidents, particularly Lyndon B. Johnson, on health care policy, and served on advisory councils of the National Institutes of Health. DeBakey also served as a consultant to governments and universities in Europe, the Eastern Bloc, and the Middle and Far East, where he helped establish health care systems, including cardiovascular surgery programs.

DeBakey's first wife, Diana, died of a heart attack in 1972. Three years later he married German actress Katrin Fehlhaber, and they had a daughter, Olga.

A prolific author, DeBakey published over 1600 articles, books and book chapters during his long career. These cover a broad range of topics, from his early studies of peptic ulcers, to lung cancer, to battle injuries and military medicine, through every aspect of cardiovascular surgery, to artificial hearts and heart transplants. He also wrote about medical education, ethics, history, and policy.

DeBakey's outstanding accomplishments earned him many awards and honors. These include the U.S. Army's Legion of Merit in 1945; the Rudolph Matas Award in Vascular Surgery in 1954; the American Medical Association's Distinguished Service Award in 1959; the Albert Lasker Award for Clinical Research in 1963; the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1969; the National Medal of Science in 1987; the United Nations Lifetime Achievement Award in 1999; and the Congressional Gold Medal in 2008. He received more than 50 honorary doctorates, and was also commemorated in the naming of departments, laboratories, and buildings at Baylor and elsewhere.

DeBakey continued doing surgery until he was 90, and estimated that during the course of his career, he had performed over 60,000 operations and trained several thousand surgeons. In 2006, he suffered a dissecting aneurysm, which was repaired by surgeons he had trained, using the techniques he had originated more than 50 years before. He made a good recovery and died two years later, on July 11, 2008, of natural causes. Once dubbed "the Texas Tornado" by cardiologist Paul Dudley White, DeBakey left an astonishing legacy of surgical innovation, medical education and research, and health care policy, as well as thousands of patients whose lives were saved by his skills.