Biographical Overview

Alan Gregg was born on July 11, 1890 to James B. and Mary (Needham) Gregg in Colorado Springs, Colorado, where his father, a Congregationalist minister, had relocated from Boston. Like his father and three elder brothers, Gregg pursued undergraduate work at Harvard, earning his BA in 1911. Although a family physician had sparked his interest in medicine at an early age, Gregg was still tempted by a writing career (he served as President of the Harvard Lampoon in his senior year). Nevertheless, following the advice of Arthur T. Lyman, the grandfather of a student he tutored (who later helped finance his medical education), Gregg continued on to medical school. When the First World War began in 1914, he considered enlisting in Canada (the United States had not yet entered the war), but Lyman persuaded the young man that he would be more useful to the war effort if he first completed medical school. Gregg thus finished his schooling in 1916 and, following a year-long internship at Massachusetts General Hospital, served in France from October 1917 to February 1919 as part of the Harvard Medical Unit in the British Army Medical Corps.

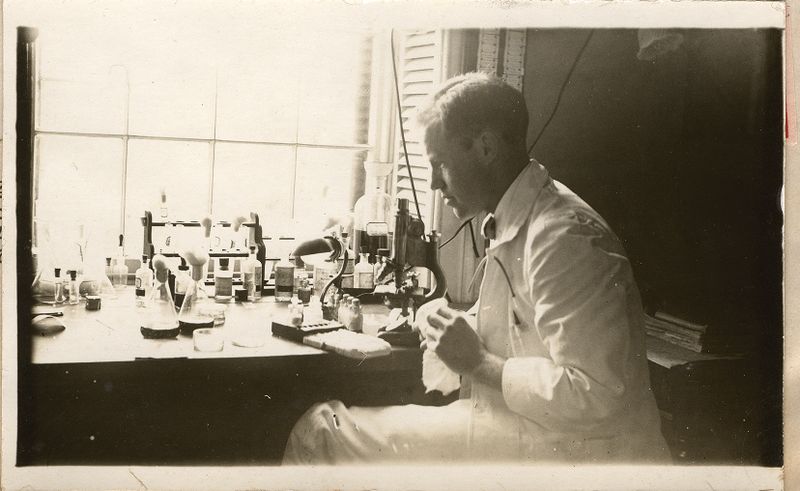

Gregg had decided to pursue a public health career during his clinical internship year. Distressed by the steady stream of patients suffering from advanced chronic illness, for whom little or nothing could be done, he had come to appreciate the importance of preventive medicine. Meeting with the Rockefeller Foundation's Victor Heiser in 1916, Gregg became convinced that advanced public health practice was the best way to bring medical knowledge to bear on disease prevention. The Rockefeller Foundation had been established in 1913 to help promote a wide range of activities in science, the arts, agriculture, civic education, medicine, and public health in the United States and abroad. Its public health work--including a successful hookworm control program in the southern United States--was intended in part to apply the medical knowledge generated at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, founded in 1901. The International Health Board provided unparalleled opportunities for young physicians interested in the growing field of public health practice and administration. Accordingly, after discharge from the medical corps, Gregg met with Wickliffe Rose, Director of the International Health Board, who offered him several choices of overseas assignments. Gregg selected Brazil, and in March 1919 began a three-year assignment, working with Lewis Hackett to extend the foundation's hookworm control project to the South American country.

Toward the end of Gregg's Brazilian term of service in 1922, Richard Pearce, Director of the Rockefeller Foundation's Division of Medical Education, invited him to become Associate Director of the division, whose mission was to develop the teaching of scientific medicine around the world. Gregg returned to the United States in April 1922, and while contemplating Pearce's offer, he rekindled his acquaintance with Eleanor Barrows, an old friend from Colorado; the couple married in July. Gregg accepted Pearce's offer, officially joining the Medical Education Division on July 31, 1922.

Just two months later, Pearce left his new associate director in charge of the Medical Education Division's New York office, traveling to Europe for seven months to survey medical education there. Gregg learned the ropes quickly and carried out his own surveys of medical and health resources in Colombia and Mexico the following year. In 1924, Pearce sent Gregg to Paris to oversee a planned expansion of the division's activity in Europe.

Gregg worked out of the Rockefeller Foundation's Paris office from 1924 until 1930. He oversaw the fellowship program and all foundation activities supporting medical education and research in Europe. These efforts typically included surveys of countries where grants might be made, as well as funding recommendations for general medical education support and specific research projects. Gregg personally surveyed and wrote reports about medicine in Italy, Ireland, and Russia, among others. The reports, insightful models on the state of medicine in those countries, also reveal the biases and paternalism of many Americans intent on bringing their know-how and money to the Old World.

When Pearce died in 1930, Max Mason, the new President of the foundation, called Gregg back to New York to direct the Medical Sciences Division, created after a recent reorganization of the foundation. He remained in this post until the 1950s, overseeing the foundation's new efforts to support more focused medical research, even though he personally favored continuation of general medical education reform that Abraham Flexner pioneered in the foundation's earlier years.

During the 1930s, Gregg's division supported important new medical research, including clinical trials at Queen Charlotte's Maternity Hospital in London of new sulfanilamide "miracle" drugs to combat puerperal fever. The division also provided broad support for the important new field of psychiatry. From his work in the 1920s, Gregg had become familiar with leading European figures in psychiatry, neurology, and brain research; moreover, both he and Pearce had encouraged the expansion of this field in the United States, beginning at the Yale Institute of Human Relations in 1929. In subsequent years, Gregg funded a new psychiatry department at the University of Chicago and improvements in teaching psychiatry at Harvard, Johns Hopkins, Washington University in St. Louis, Columbia, and other leading American medical schools. Reminiscent of earlier large Rockefeller projects was a $1.25 million grant for Wilder Penfield's Neurological Institute at McGill University in Montreal. Additionally, Gregg's division supported researchers in Germany (until the Nazis were firmly in power), and in Britain, especially at Maudsley Hospital in London, in fields such as psychiatry, psychology, neuro-anatomy, mental illness, and brain chemistry.

Gregg supported established, successful researchers such as Nobel Prize winner Albert Szent-Györgyi at the University of Szeged in Hungary and Henry Dale in London. Beyond such support, the medical fellowship program Gregg oversaw continued to scour Europe for promising young researchers and to match them with the best laboratories in Western Europe and North America. Although the research awards were modest in size, these fellowships (over 1,250 through 1950) had a cumulative effect on both sides of the Atlantic. American Nobel laureate Robert Millikan called the fellowships "the most effective agency in the scientific development of American life and civilization that has appeared on the American scene in my lifetime."

The start of World War II in Europe immediately affected Rockefeller Foundation programs, even though the Paris office was not evacuated until shortly before the fall of France in May 1940. From then until America's entry into the war, Gregg began to recognize the limits of the foundation's activities and tried to anticipate the crucial role the organization might play in postwar Europe. Despite his foresight, the Rockefeller Foundation's importance diminished after 1945--the enormous task of rebuilding Europe captured energies that might have gone into private philanthropic efforts and the prevailing tide of social construction tended toward government action and away from private philanthropy, in scientific and medical research as elsewhere. In addition to these trends, changes in the foundation's leadership and board led to significantly greater emphasis on short-term grants and further diminished medicine as a priority; nevertheless, some noteworthy large projects, such as Alfred Kinsey's study of human sexuality, received support.

Increasingly unhappy with his position, in March 1951, Gregg wrote a confidential letter to new Rockefeller Foundation President Chester Barnard admitting disappointment with the situation and requesting more freedom to address broader issues. The following month at the April trustees meeting, Barnard recommended a merger of the International Health Division and the Division of Medical Sciences into a Division of Medicine and Public Health under Gregg's former assistant, Robert Morison. The merger approved, Gregg became the foundation's Vice President. He was thus able to pursue his growing interest in writing and speaking about medicine and its broader role in society, tasks which had increasingly occupied his time after the war.

In this new position, Gregg served as the first Chairman of the Advisory Committee for Biology and Medicine of the Atomic Energy Commission from 1947 to 1953, as a member of the National Advisory Mental Health Council of the United States Public Health Service from 1946 to 1950, and as head of the sub-committee of the Task Force on Medical Services of the Second Hoover Commission on Organization of the Executive Branch of Government from 1954 to 1955. The latter group took the lead in recommending the creation of the National Library of Medicine, which Congress authorized in 1956. During this time, Gregg also received numerous awards, including the French Legion of Honor and a special Lasker Award in 1956. He traveled, lectured, and published about physicians, medical education, and research worldwide until retiring in 1956. Alan Gregg died on June 19, 1957.